Edgar E. Joralemon

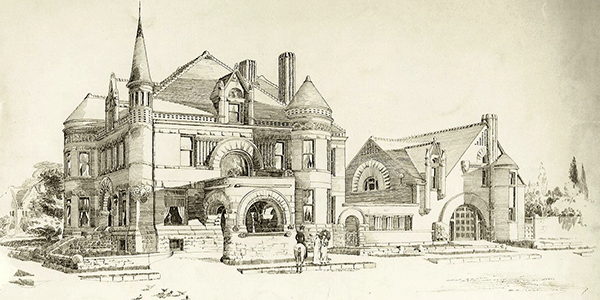

I came to learn about Edgar Eugene Joralemon because I bought the Dr. Henry Elmer Holmes House, 1887 (1418 Park Avenue, NW corner East 15th Street & Park Avenue Minneapolis, Minnesota) in the summer of 1981. A friend in realty showed me a 2 for 1 wrecked building deal near downtown Minneapolis for only $45,000. Holmes House came with an even older house on the same lot, the Jacob H. Heisser House ca. 1874 (636 East 15th Street.) It had been moved to “the rear of the lot” in 1887 preceding the construction of Holmes House. Park Avenue Minneapolis was becoming fashionable. I’d bought two condemned buildings as I later found out.

After I graduated from art school I had a dream of restoring historic buildings, preserving our architectural heritage and making money at it. I was acquainted with people who had made good money renovating buildings in the 1970s. After I’d made my fortune I could retire early and make art. Remember, I was only twenty-five. Part of the original plan was to turn Holmes House into a small office building and take advantage of a federal twenty-five percent Historic Tax Credit to help finance the venture. This would help create enough money to do a really good restoration, or so I thought. This meant getting Holmes House on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), which had a process starting in Minneapolis and Minnesota’s historic preservation offices.

The premise of the NRHP nomination was that Holmes House was an important and surviving example of an eclectic blend of the Queen Anne, Shingle Style, and Romanesque architectural styles that Edgar E. Joralemon pioneered in Minneapolis and excelled in. Once upon a time Minneapolis had hundreds of hybrid buildings that excited the eye in their textures, colors and variety. Unfortunately, most of them were built on prime real estate; real estate that would become today’s highways, parking lots, apartments, businesses and government agencies. Unfortunately for Holmes House, a survivor, the deciding staff bureaucracy in Minneapolis and the Minnesota State Preservation Office disagreed and fought my NRHP nomination for seven years. I have often wondered IF only I’d given my local city council-members some campaign contributions I may have been taken more seriously.

Anyway, being young and idealistic and under the naïve idea that merit counted, I figured “all” I had to do was to research and “write the book” on Edgar E. Joralemon and his work and the powers would realize what a pioneer architect Edgar E. really was and support my NRHP nomination. It didn’t work out that way at all.

Though I had some self-taught experience in carpentry and handyman skills I’d never done real estate development before and had no training in it. Accordingly, I barreled ahead with faulty assumptions and made many mistakes. The first was presuming that I could lease parking from the very large empty parking lots directly adjacent to Holmes House. This lead me to first 100% renovate 636 East 15th Street into a duplex with two large one-bedroom apartments (up & down.) Retrospect indicates that I should have torn 636 down for five parking spaces because in spite of the surplus of off-street parking nobody wanted to lease it. By 1982 with a 13.75% mortgage interest rates I began learning the hard way the travails of being a small inner-city landlord and the interconnections of politics and real estate. Ronald Reagan had been elected president and vowed to stop the government-induced inflation I grew up with. He succeeded, but the sky-high interest rates helped make my dreams of saving Minneapolis’s inner-city historic buildings very difficult.

Thinking it was just a matter of time until Holmes House would be on the NRHP, I made many classic business mistakes. Over-extending myself by buying additional buildings at top of the market prices and high interest rates being the major folly. In 1983, for example, I bought the Hinkle-Murphy House, 1886, by William Channing Whitney at 619 South 10th Street Minneapolis. It was bigger and had lots of parking. It was also much easier to get on the NRHP. The NRHP nomination was easier because William Channing Whitney was a well-known society architect of his day and Mr. Hinkle and Mr. Murphy well respected businessmen in Minneapolis. Murphy was once the owner of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune newspaper.

At the time it was a rooming house (shared kitchen and bathrooms) with about sixteen tenants. I paid way too much for it with a very short contract for deed. I had convinced myself Hinkle-Murphy had all the things Holmes House lacked in becoming a small historic office building on the NRHP. I was right about the NRHP, but my market timing was terrible. When the balloon payment came due, in less than two years, the contract owner wanted tens of thousands of dollars more for a six-month extension. By December of 1984 it was time to cut my substantial losses and I gave it back to the greedy bastard. He took my plans, kicked out all of the tenants and hired incompetent people to renovate it to my plans. He went backwards.

In the summer of 1988 it was arsoned and looted. However, because of its fireproof construction and my getting it on the NRHP #84001438 Hinkle-Murphy House, 1886 still stands today at 619 South 10th Street, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

I continued to research Edgar Joralemon, the Holmes family... any angle to prove Holmes House worthy of the NRHP. In spite of multiple re-writings and reams of original research, one Minnesota State Preservation Office staff member could not accept Holmes House’s architectural significance. She also never would tell Paul Clifford Larson, the nomination author, or me, what information it would take to convince her that Holmes House was worthy of the NRHP. I decided to plead my case directly to the State Historic Preservation Commission. In June 1988 I made my presentation with the help of others and waited for the verdict. Eventually, Holmes House and Edgar E Joralemon did prevail, but it turned out to be anti-climatic.

Business wise, I eventually came to the realization that lacking my own parking spaces and the idea of a small historic office building was quaint, but didn’t work in the marketplace. A successful business is a growing business; they need space to expand. Holmes House really couldn’t offer that. Holmes House was already zoned for apartments and the tenants could use on-street parking if they had to. Bob Roscoe, the architect, and I changed the plan into four two-bedroom apartments. The first floor would have the bedrooms in the basement and the second floor bedrooms would be in the attic.

The spring of 1988 came unusually early. It was warm enough to get underway in March. The plan was to start with the interior framing and foundation, then work on the exterior. We went to work. Reframing rotted areas, headers over doors and windows, doubling up floor joists all needed to be done. New footings were poured in the basement to support two stairways running from the basement to the attic. By June the new stairs had been framed. The internal framing was almost done. Things were going well on the project, but there were ominous signs in the neighborhood.

An arsonist seemed to be about. There had been a few suspicious fires in Elliot Park at 624 East 15th Street and at the Hinkle-Murphy House at 619 South 10th Street. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much I could do about it. Holmes House was a wooden building and it hadn’t rained in months. I thought that since Holmes House had survived years of being vacant it would be lucky. I was wrong, and the arsonist struck at dawn on June 21, 1988. Within an hour, all of the work of seven years was reduced to a pile of burned timbers. Talk about a life-changer.

After the fire department left it was time to go home and call the crew and tell them the job burned down. My tenants in 636 were in shock too. They had wakened when their windows broke from the heat of the fire. Thank goodness 636 had stucco walls and new Class A fireproof shingles. They both ended up moving soon after. After other chores got done it was time to sit down and cry and chart a new course.

If you have information to share about Edgar Joralemon, please contact me.

EE Joralemon Links · Interactive Map

After I graduated from art school I had a dream of restoring historic buildings, preserving our architectural heritage and making money at it. I was acquainted with people who had made good money renovating buildings in the 1970s. After I’d made my fortune I could retire early and make art. Remember, I was only twenty-five. Part of the original plan was to turn Holmes House into a small office building and take advantage of a federal twenty-five percent Historic Tax Credit to help finance the venture. This would help create enough money to do a really good restoration, or so I thought. This meant getting Holmes House on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), which had a process starting in Minneapolis and Minnesota’s historic preservation offices.

The premise of the NRHP nomination was that Holmes House was an important and surviving example of an eclectic blend of the Queen Anne, Shingle Style, and Romanesque architectural styles that Edgar E. Joralemon pioneered in Minneapolis and excelled in. Once upon a time Minneapolis had hundreds of hybrid buildings that excited the eye in their textures, colors and variety. Unfortunately, most of them were built on prime real estate; real estate that would become today’s highways, parking lots, apartments, businesses and government agencies. Unfortunately for Holmes House, a survivor, the deciding staff bureaucracy in Minneapolis and the Minnesota State Preservation Office disagreed and fought my NRHP nomination for seven years. I have often wondered IF only I’d given my local city council-members some campaign contributions I may have been taken more seriously.

Anyway, being young and idealistic and under the naïve idea that merit counted, I figured “all” I had to do was to research and “write the book” on Edgar E. Joralemon and his work and the powers would realize what a pioneer architect Edgar E. really was and support my NRHP nomination. It didn’t work out that way at all.

Though I had some self-taught experience in carpentry and handyman skills I’d never done real estate development before and had no training in it. Accordingly, I barreled ahead with faulty assumptions and made many mistakes. The first was presuming that I could lease parking from the very large empty parking lots directly adjacent to Holmes House. This lead me to first 100% renovate 636 East 15th Street into a duplex with two large one-bedroom apartments (up & down.) Retrospect indicates that I should have torn 636 down for five parking spaces because in spite of the surplus of off-street parking nobody wanted to lease it. By 1982 with a 13.75% mortgage interest rates I began learning the hard way the travails of being a small inner-city landlord and the interconnections of politics and real estate. Ronald Reagan had been elected president and vowed to stop the government-induced inflation I grew up with. He succeeded, but the sky-high interest rates helped make my dreams of saving Minneapolis’s inner-city historic buildings very difficult.

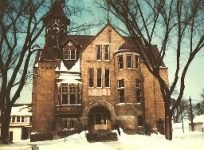

Thinking it was just a matter of time until Holmes House would be on the NRHP, I made many classic business mistakes. Over-extending myself by buying additional buildings at top of the market prices and high interest rates being the major folly. In 1983, for example, I bought the Hinkle-Murphy House, 1886, by William Channing Whitney at 619 South 10th Street Minneapolis. It was bigger and had lots of parking. It was also much easier to get on the NRHP. The NRHP nomination was easier because William Channing Whitney was a well-known society architect of his day and Mr. Hinkle and Mr. Murphy well respected businessmen in Minneapolis. Murphy was once the owner of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune newspaper.

At the time it was a rooming house (shared kitchen and bathrooms) with about sixteen tenants. I paid way too much for it with a very short contract for deed. I had convinced myself Hinkle-Murphy had all the things Holmes House lacked in becoming a small historic office building on the NRHP. I was right about the NRHP, but my market timing was terrible. When the balloon payment came due, in less than two years, the contract owner wanted tens of thousands of dollars more for a six-month extension. By December of 1984 it was time to cut my substantial losses and I gave it back to the greedy bastard. He took my plans, kicked out all of the tenants and hired incompetent people to renovate it to my plans. He went backwards.

In the summer of 1988 it was arsoned and looted. However, because of its fireproof construction and my getting it on the NRHP #84001438 Hinkle-Murphy House, 1886 still stands today at 619 South 10th Street, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

I continued to research Edgar Joralemon, the Holmes family... any angle to prove Holmes House worthy of the NRHP. In spite of multiple re-writings and reams of original research, one Minnesota State Preservation Office staff member could not accept Holmes House’s architectural significance. She also never would tell Paul Clifford Larson, the nomination author, or me, what information it would take to convince her that Holmes House was worthy of the NRHP. I decided to plead my case directly to the State Historic Preservation Commission. In June 1988 I made my presentation with the help of others and waited for the verdict. Eventually, Holmes House and Edgar E Joralemon did prevail, but it turned out to be anti-climatic.

Business wise, I eventually came to the realization that lacking my own parking spaces and the idea of a small historic office building was quaint, but didn’t work in the marketplace. A successful business is a growing business; they need space to expand. Holmes House really couldn’t offer that. Holmes House was already zoned for apartments and the tenants could use on-street parking if they had to. Bob Roscoe, the architect, and I changed the plan into four two-bedroom apartments. The first floor would have the bedrooms in the basement and the second floor bedrooms would be in the attic.

The spring of 1988 came unusually early. It was warm enough to get underway in March. The plan was to start with the interior framing and foundation, then work on the exterior. We went to work. Reframing rotted areas, headers over doors and windows, doubling up floor joists all needed to be done. New footings were poured in the basement to support two stairways running from the basement to the attic. By June the new stairs had been framed. The internal framing was almost done. Things were going well on the project, but there were ominous signs in the neighborhood.

An arsonist seemed to be about. There had been a few suspicious fires in Elliot Park at 624 East 15th Street and at the Hinkle-Murphy House at 619 South 10th Street. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much I could do about it. Holmes House was a wooden building and it hadn’t rained in months. I thought that since Holmes House had survived years of being vacant it would be lucky. I was wrong, and the arsonist struck at dawn on June 21, 1988. Within an hour, all of the work of seven years was reduced to a pile of burned timbers. Talk about a life-changer.

After the fire department left it was time to go home and call the crew and tell them the job burned down. My tenants in 636 were in shock too. They had wakened when their windows broke from the heat of the fire. Thank goodness 636 had stucco walls and new Class A fireproof shingles. They both ended up moving soon after. After other chores got done it was time to sit down and cry and chart a new course.

If you have information to share about Edgar Joralemon, please contact me.

EE Joralemon Links · Interactive Map

1880s

1880s 1890s

1890s Ellis & Levering

Ellis & Levering Holmes House

Holmes House Joralemon Family

Joralemon Family New York

New York Partners

Partners St. Paul (MN) Public Library

St. Paul (MN) Public Library Unidentified

Unidentified